Rooms We Made Safe:

On Sisterhood, Solace, and the Radical Intimacy of Michella Bredahl at Huis Marseille

There are exhibitions you look at, and then there are exhibitions you enter. Michella Bredahl’s Rooms We Made Safe, currently on view at Huis Marseille, is unmistakably the latter. It’s a study of sisterhood, womanhood, and the domestic setting, unfolding like a memoir you can walk through.

I visited with my oldest sister, a choice that felt instinctive. Bredahl’s work pulses with the idea of sisterhood: the fierce, unspoken support, the shared memory, the knowing. Together, we stepped into Bredahl’s rooms, those that feel lived, ruptured, reclaimed, and suddenly we were not just spectators, but participants in the emotional circuitry of the exhibition.

The Perfect Setting: Huis Marseille as a Spatial Echo of the Work

Huis Marseille’s layout, a chain of adjoining, domestic-scale rooms, reinforces Bredahl’s central themes. The architecture encourages a kind of quiet immersion: you enter each space almost as though entering a bedroom or a living room, not a gallery. This intimate spatial rhythm mirrors the environments Bredahl photographs: rooms that function as sanctuaries, hiding places, and emotional archives.

The museum’s structure also underscores the fragmented continuity of Bredahl’s narrative. Each room feels self-contained, yet part of a larger story, much like the domestic spaces that shape women’s lives across time.

Bedrooms as Solace, and as ‘Painful Refuge’

One of the most resonant threads throughout the exhibition is the bedroom: an intimate world of soft chaos, rumpled bedding, strewn clothes, half-light. In Bredahl’s universe, the bedroom is not merely a backdrop but also a psychic landscape.

It is where women retreat to survive.

It is where they unravel.

It is where they make sense of themselves.

This duality of solace and confinement echoes sharply with Virginia Woolf’s assertion that women need "a room of one’s own." Woolf imagined a room as a haven: a sanctuary of autonomy, a quiet site for creation. But she also understood that rooms could be prisons, shaped by social, financial, or emotional constraint. Bredahl’s bedrooms carry that same contradiction.

They are havens, places where women can finally exhale, embody femininity as energy and not performance, where softness is allowed, where they can sit in their own truth; while also they are painful refuges, small and temporary spaces where women hide from instability, addiction, poverty, or the unpredictable volatility of their environment.

Her images reveal how the bedroom is often the only space women can call their own, even when that ownership is tenuous. Yet within those four walls, they build identity, intimacy, and resilience. The bedrooms become self-authored zones in which survival and selfhood coexist.

Standing beside my sister in those rooms, I felt a familiar ache with the memory of the bedrooms we grew up in, the arguments whispered through thin walls, the comforts we built for ourselves when the world outside felt unknowable. A room can save you and break you at the same time and Bredahl understands that intimately.

Sisterhood as Shared Witnessing

Bredahl’s archive incorporates images of her own family, particularly the dynamic between her mother, herself, and her sister. Moving through the show with my sister underscored how the exhibition foregrounds women supporting, documenting, and stabilising one another within domestic contexts.

Sisterhood appears here not as sentimentality but as a structural support system, a way of enduring environments that are often unpredictable. The exhibition positions sisters (biological or chosen) as co-authors of each other’s histories

My sister and I don’t often get long afternoons together anymore, but in Bredahl’s exhibition we fell into a quiet, shared rhythm. We lingered before the photographs of girlhood: siblings brushing hair, a sister perched on a bed in a too-small room, the overlap of limbs and laughter and tension.

Bredahl’s work made us remember our old rooms: the sanctuaries we decorated, the secrets shared under duvets, the nights we turned to each other for quiet safety. It reminded us that sisterhood is its own kind of room: a structure you carry, a shelter built from years of seeing and being seen.

Women as Active Subjects, The Antithesis of the Male Gaze

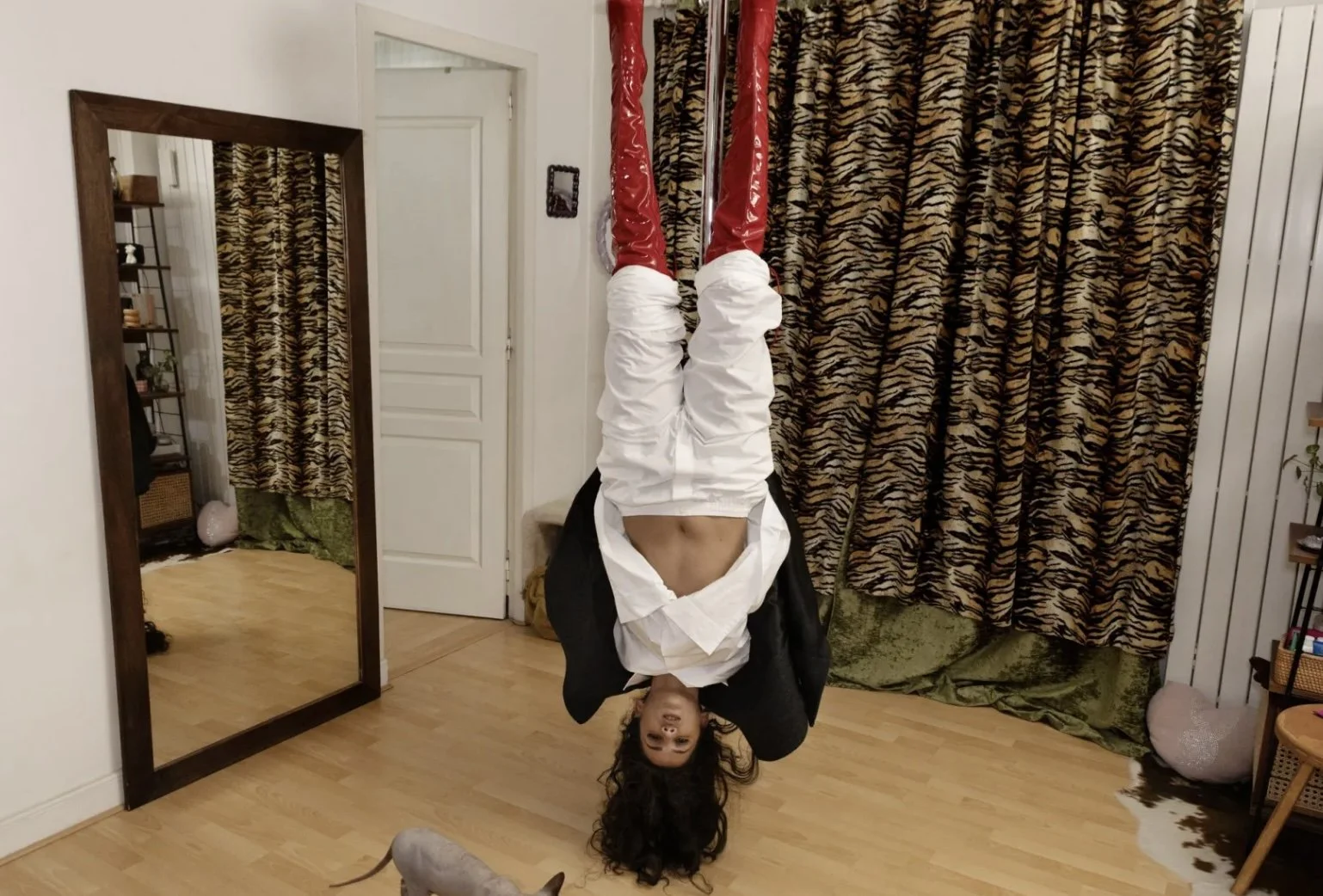

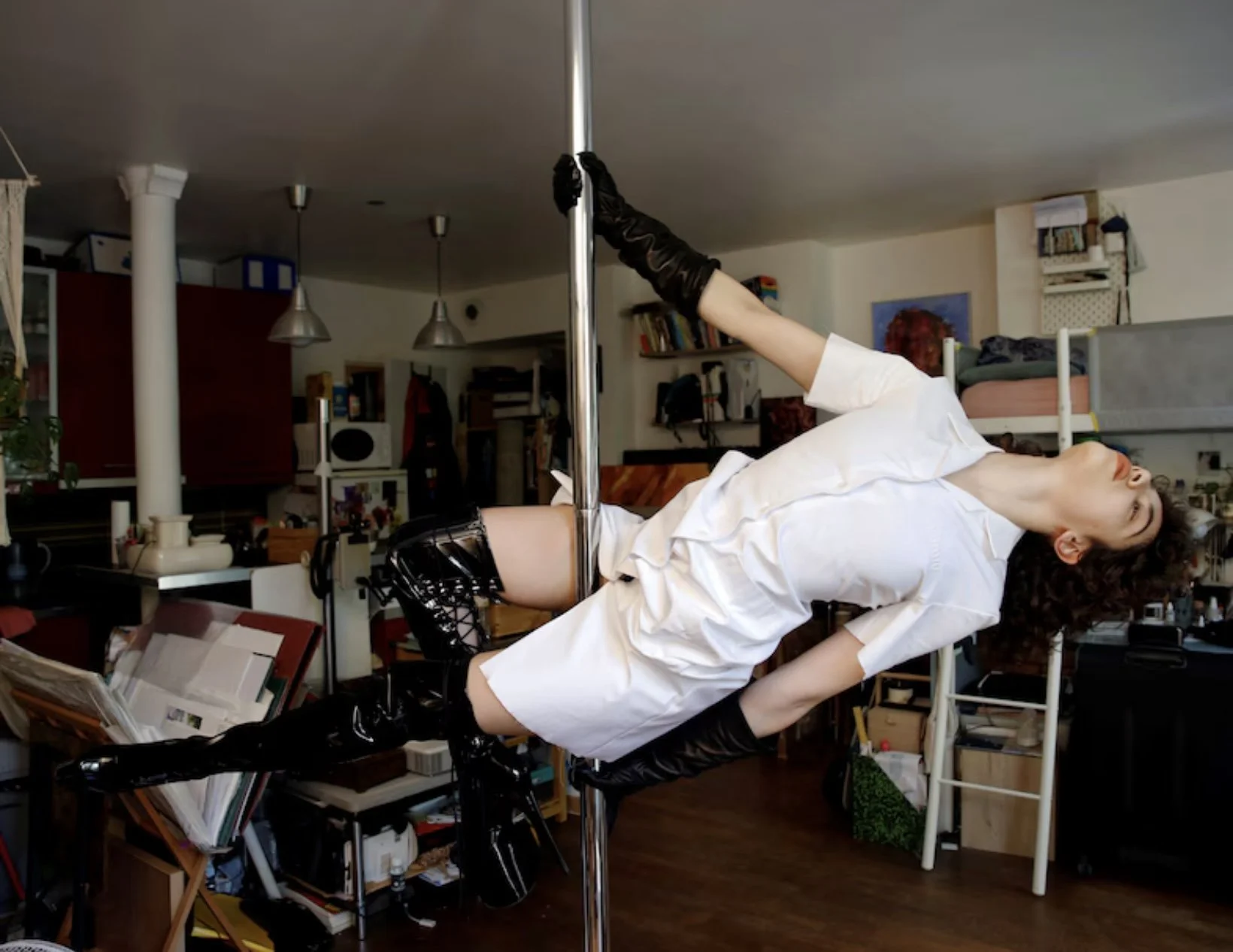

One of the subtler but most radical triumphs of Rooms We Made Safe lies in how it rejects the visual traditions that have long dominated portrayals of women. Crucially, Bredahl’s photographs stand against the conventions of the male gaze. Her subjects are not passive objects of observation; they are active participants. The women in these rooms are photographed with a collaborative agency as their expressions, their postures, and their environments contribute to an honest record of their lives.

Instead of presenting women as symbols or aestheticised figures, Bredahl positions them as archivists of their own existence. Their rooms become evidence of lived realities rather than backdrops for fantasy. This shift is central: the domestic interior is not a stage set but a context that shapes and reflects identity. Bredahl’s photographs are the direct antithesis of the male gaze. Her subjects are not positioned to be admired, consumed, or mythologised. They are not performing femininity. They are not flattened into symbols or fantasies.

Instead, they look back.

They collaborate.

They co-create the image.

Every woman in these photographs is an active participant in her own representation. Her posture, her clutter, her gaze, her room with all of these features becoming contributions to her own history. The photographs do not strip them of privacy; they illuminate their agency.

This is Woolf’s vision reframed for a contemporary lens: women documenting the interior worlds that have so often been dismissed, diminished, or hidden. Rooms become evidence. Portraits become testimony. Women become narrators of their own stories.

Lotta Volkova’s Styling: Clothes as Emotional Armour and Revelation

Clothing in Bredahl’s photographs plays an unexpectedly potent role, especially with the additions shaped by stylist Lotta Volkova. Volkova’s signature approach such as: underwear layered as outerwear, slip dresses paired with athletic pieces, lingerie exposed rather than concealed, mirroring the emotional openness of the images.

Her styling amplifies three crucial dynamics:

Turning vulnerability into authorship.

When underwear becomes outerwear, it reconfigures privacy. What is usually hidden becomes chosen visibility and not eroticised, but empowered. This only emphasises the collapse between public and private spaces in Bredahl’s work.

Resisting pettification.

Volkova’s aesthetic is fun, expansive, multifaceted. It fits the honesty of Bredahl’s imagery: nothing curated for the male viewer, everything arranged in service of femininity as an energy and resisting the glamorisation or traditional notions.

It speaks to contemporary womanhood - complex, layered, unguarded.

This is the wardrobe of women at home: half-dressed, mid-transition, comfortable in their own skin. It deepens the sense that the room is not a stage, but an extension of their inner life. Volkova’s touch doesn’t decorate the photograph but intensifies their emotional fidelity, reinforcing the sense of women existing on their own terms within domestic settings.

Motherhood, Addiction, and the Expanded Archive

One of the most impactful sections is the inclusion of Bredahl’s mother, both as subject and image-maker. Her photographs, shown alongside accounts of her struggles with addiction, introduce a generational dimension to the exhibition. They contextualise Bredahl’s own childhood images within a broader cycle of instability, creativity, and resilience.

This addition prevents the exhibition from becoming purely autobiographical; it situates the private within the socio-political. It shows how addiction, class, motherhood, and domestic precarity intersect - and how photography becomes a means of documenting and understanding those intersections.

Why Bredahl’s Exhibition Matters

Bredahl’s exhibition provides an important counterpoint to mainstream portrayals of women in domestic spaces. It shows the home as a site of both vulnerability and self-definition, and foregrounds the autonomy of women within their own visual narratives.

By combining personal archive, collaboration, and a critical lens on domesticity, Bredahl challenges assumptions about who gets to make images, who gets to be represented truthfully, and how women’s lives are recorded historically.

Visiting the exhibition with my oldest sister made these questions feel especially present. It highlighted how domestic spaces and shared memories continue to shape us, and how photography can reframe these spaces not as passive backdrops, but as active parts of women’s stories.

Rooms We Made Safe succeeds because it uses domestic space not as an aesthetic comfort zone but as a critical lens. It interrogates how women inhabit rooms, how they are shaped by them, and how these spaces become repositories of memory, trauma, and identity.

Seen within the intimate architecture of Huis Marseille and in my case, alongside my own sister, the exhibition underscores how deeply rooms and relationships inform one another.

It is a thoughtful, precise, and necessary exploration of what it means for women to be seen authentically, on their own terms, in the rooms that have shaped their lives.